This is the 2nd of the blog posts series that talks about ARM64 performance investigation for .NET 5. You can read my previous blog at Part 1 - ARM64 performance of .Net Core.

In this post, I will describe the implication of weakly-ordered memory model of ARM64 on generated code by .NET and how we got good wins in ARM64 for some methods present in System.Collections.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary.

Memory ordering

ARM architecture has weakly ordered memory model. The processor can re-order the memory access instructions to improve the performance of the processor. It can rearrange the instructions to reduce the time processor takes to access memory. The order in which user has written the code is not guaranteed to be executed in same order and can be weakly defined depending on the memory access cost for given code. This is fine for single core machine but imagine a situation in a multi-threaded program ran on multi-core machine where core A is about to read a memory that just got overwritten by core B. The user might have intended to have code that is executed by core A to read memory before the code executed by core B writes. As you can see, this can easily get complicated and problematic. Luckily, in such situations, there are instructions to tell processors not to re-arrange memory access at a given point inside code. The technical term for such instructions that restricts this re-arrangement is called “memory barriers”. The dmb instruction in ARM64 acts as a barrier prohibiting the processors from moving the instructions across the fence. There are various types of barriers depending on if the user intent to restrict the re-ordering of just memory loads or memory stores or both. There are instructions to also have a barrier one-way i.e. instructions can be moved from after the barrier to before the barrier but not other way round or vice-versa. More details can be read in ARM documentation or some of the excellent articles here and here.

C# memory barrier using volatile

There are various ways to express the desire in C# to add memory barriers. One such way is by using volatile variable in C#. With volatile variable, it is guaranteed that the runtime, JIT or the processor will not rearrange reads and writes to memory locations for performance. To make this happen, RyuJIT would emit dmb (data memory barrier) instruction for ARM64 every time there is an access (read/write) to a volatile variable.

For example, below is the C# code taken from microbenchmarks. It does a volatile read of local field _location.

public class Perf_Volatile

{

private double _location = 0;

[Benchmark]

public double Read_double() => Volatile.Read(ref _location);

}

The generated relevant machine code of Read_double for ARM64 is:

; Assembly listing for method Program:Read_double():double:this

; Emitting BLENDED_CODE for generic ARM64 CPU - Windows

G_M49790_IG02:

91002000 add x0, x0, #8

FD400000 ldr d0, [x0]

D50339BF dmb ishld

The code first gets the address of _location field, loads the value in d0 register and then execute dmb ishld that acts as a data memory barrier.

Although this guarantees the memory ordering, there is a cost for it. The processor must now guarantee that all the data access done before the memory barrier is visible to all the cores after the barrier instruction. This means that the barrier requires all memory operations to complete before letting the cores cross the barrier instruction and this is time consuming.

System.Collection.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary

While going through the benchmarks that are slower on ARM64, I noticed that a simple benchmark that gets the count of number of items stored inside System.Collection.Concurrent.ConcurrentDictionary was slower. On inspecting GetCountInternal, I noticed that there was an access of volatile variable _tables inside a loop.

Here is the code before it was fixed:

private sealed class Tables

{

// ..

internal volatile int[] _countPerLock; // The number of elements guarded by each lock.

// ..

}

private volatile Tables _tables;

private int GetCountInternal()

{

int count = 0;

// Compute the count, we allow overflow

for (int i = 0; i < _tables._countPerLock.Length; i++)

{

count += _tables._countPerLock[i];

}

return count;

}

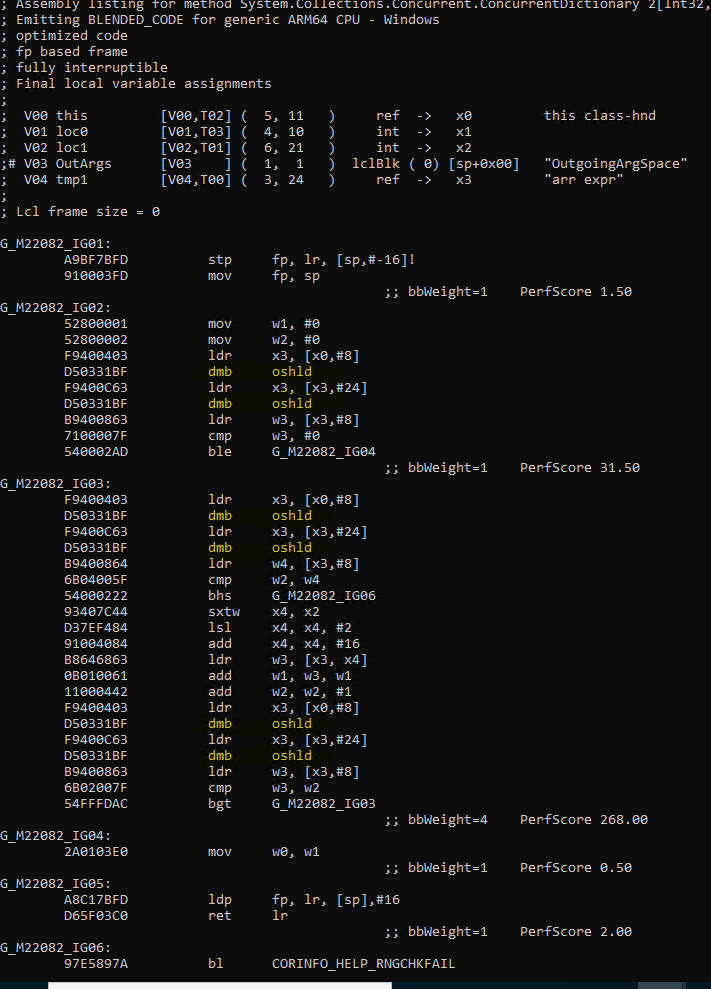

For this method, we generated ARM64 code having memory barrier instruction inside a loop. Here is the generated assembly code:

Here, IG03 is a loop and the 4 yellow highlighted ones inside this block are the memory barrier instructions. Each pair is present to access two volatile variables _tables and _tables._countPerLock. Accessing volatile variable in a loop is sensible because different thread can update the value present in the variable, and we want to ensure that this doesn’t happen while we are calculating the count. However the code already takes appropriate locks before executing the GetCountInternal() method. That means, the GetCountInternal() method is guaranteed to execute by one thread at a time. With that being present, it is fine to cache the volatile variable value out of loop and use it inside the loop. That will change the C# code to something like this:

private int GetCountInternal()

{

int count = 0;

int[] countPerLocks = _tables._countPerLock;

// Compute the count, we allow overflow

for (int i = 0; i < countPerLocks.Length; i++)

{

count += countPerLocks[i];

}

return count;

}

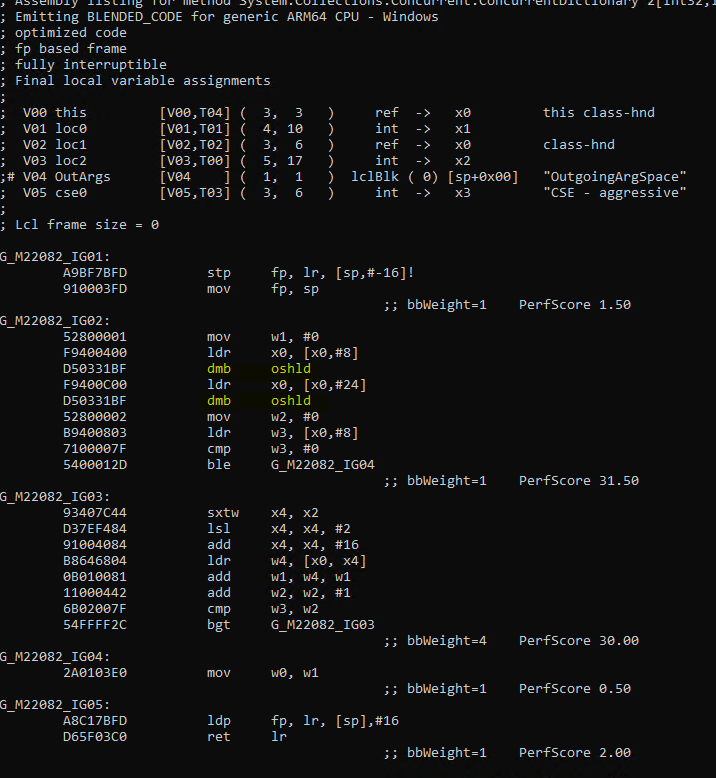

Here is the generated ARM64 code after the change.

If you see there are no more memory barrier instructions inside the loop IG03 now. This simple change gave approxiametely 30% win in the corresponding benchmark. The fix to hoist volatile variable access out of loop was merged. In it, I was able to also hoist the access for some other methods CopyTo, GetKeys and GetValues. I am pretty sure there are other places in .NET code base where similar code is there and someday, I need to sit and scan through it to get more performance wins.

Conclusion

To summarize, C# developer should pay careful attention while using various locking APIs or language features such as volatile. They come with a cost and different architecture have different cost. Thorough code review and questioning the code you write is the key to write efficient code for cross-architecture.

Namaste!